As you will see, I dedicated the story to them and told a little of their wartime stories in my Acknowledgments at the end of the book, but I asked my mother, Shirley, if she would write in more detail about her own experiences as a child evacuated from London, and tell us more about my father’s time as a young British soldier.

Shirley: Caroline very kindly dedicated her YA debut novel, Wait for Me, to us, her mum and dad. In her Acknowledgments at the end, she thanks us for talking to her throughout her life about our own experiences. It amuses me that the book is regarded as historical fiction when it is in fact set in a period of our lives, but I wanted to put her book into perspective by recording some of what happened to real people during a devastating time in the world. There are many such stories, but here are ours.

I was eight years old when war was declared on September 3rd, 1939. On the Friday before that, however, my distraught mother took us to the end of the street to await my father’s return home from work, and the very next day my six year old sister, Sylvia, and I were driven from Surrey to a village called Churchill in Oxfordshire to live with a grandmother we barely knew, along with one of our cousins, Gwen, who arrived from Birmingham. My grandmother gardened, kept a pig and hens, and ran the village newspaper delivery service, so although her quiet cottage life was suddenly disrupted, she did gain some delivery girls!

Sylvia, Gwen and I attended the village school run by a headmaster who had just arrived from East London with his evacuated pupils, as much in a state of shock as we were. We settled into village life and enjoyed our freedom to roam the countryside but we missed our parents and our baby sister, Freda, who had remained in London.

|

| 1940: Shirley (center) with younger sister Sylvia and their uncles, Harry and Arthur, who worked in reserved occupations during the war |

My father was a builder, which was a reserved occupation, meaning he was not called up to the army because he was needed to stay back to rebuild after any bomb damage. Of course, this meant that Mum, Dad and the baby were in London throughout the severe bombing of the London Blitz. However, my mother’s five brothers were all called up to serve in the Army and Royal Air Force. Thankfully, they all survived the war.

My sister and I were eventually taken back to London in 1942 and so were there during the period where the Germans were bombing the city with the doodle bugs (V1’s) and the rockets (V2’s), and much of our time at school was spent in concrete shelters. At home, we slept in a Morrison shelter which served as our dining table during the day and bed at night for the children. We also had an Anderson shelter in the garden but that was always a bit damp and dank most of the year, though it made a great place to play during the hot summer months.

Anderson shelters (left) and Morrison bomb shelters (right) were named

after the government ministers who introduced them.

Sugar rationing was particularly hard for us children. During the war, we were allowed only about 2-4 ounces per week. We used to suck on Horlick’s tablets instead of sweets (Horlicks was a night time drink to help you sleep), and my dad would bring us beetroot from his allotment as another sweet treat, which we ate with Salad Cream.

|

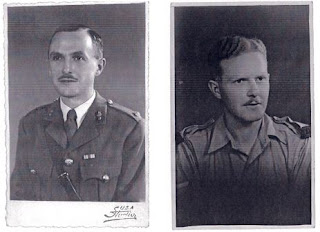

| Frank and Archie |

|

| Billy and Eric |

Meanwhile, the next two brothers. Billy and Eric, joined up and were trained to take part in the D-day landings on 6th June 1944. Billy crossed over on D-day itself, though Eric got left behind with his tank crew until the following morning. On the other side of the Channel, in attempting to find his own unit, Eric found Billy’s unit instead, and stayed until daylight before continuing on to join his own men.

|

| Jimmie, 1944 |

|

| Archie’s grave is in the military cemetery in Benghazi, Libya, and is looked after by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission |

Jimmie’s mother, Isabella, wrote weekly to all her sons and they all wrote regularly home, and we still have a good number of those letters. She had four of her five sons home again by 1949. Archie had been married for just three months before he was sent overseas and his young widow, Ellen, remained a much-loved member of the Sibbald family until she died in 1993 in her eighties. Ellen had been so devoted to Archie and to his memory, she had never remarried.

So, although I was a child, I was not entirely protected from the worries and anxieties as the war progressed, and of course, Jimmie was old enough to see service. Looking back now, and remembering the death and destruction which happened to military servicemen and servicewomen, and to civilians, across all the theatres of the war, I know that it is important that the stories of all those lived through World War Two, and especially the stories of those who died, must never be forgotten.

In Wait For Me, Lorna’s story is a poignant reminder of the war, much as I experienced it. Slightly older than me, she was strong enough to take on some of the farm duties, along with the lovely Land Girl, Nellie, whose roots and home were in London, hundreds of miles to south. Lorna’s brothers were both serving their country and this was a source of worry for Lorna and her overworked farmer father. Paul, the German POW brought to work on the farm, so far from home, having been conscripted at a young age and having suffered terrible injuries.

These two young people, brought together in such difficult circumstances but learning that they were both part of the same human race, had to fight their own prejudices and feelings, as well as those of the community in which they lived. For me, Caroline’s story captures the essence of East Lothian, and of an ordinary family battling on to help keep the nation fed and, to use a cliché, to keep the home fires burning until sons and brothers, and land girls, were able to return home.

In this past year, we have been remembering and mourning again the battles of the First World War, in particular the Battle of the Somme in 1916 where 16,000 soldiers were killed on one day. In just a couple of years, we will mark the 80th anniversary of the start of World War Two. War is a ghastly and terrifying experience, and I hope and pray that one day the world’s citizens will learn to live peacefully with each other.

|

| Lest we forget |